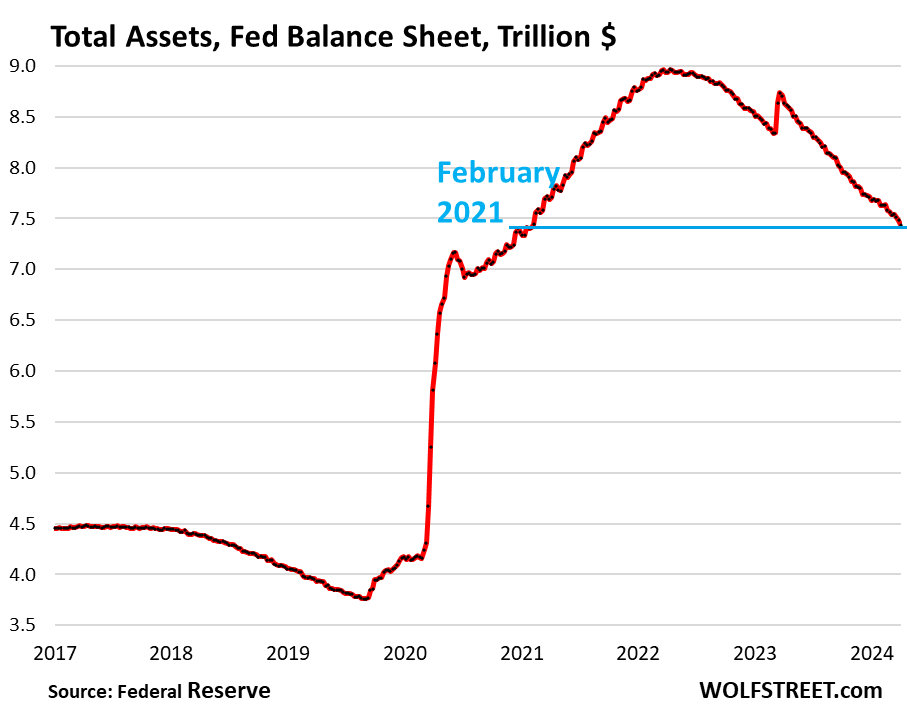

April 4, 2024 | Fed Balance Sheet QT: -$1.53 Trillion from Peak, to $7.44 Trillion, Lowest since February 2021. The BTFP Plunged by $34 Billion

Total assets on the Fed’s balance sheet fell by $99 billion in March, to $7.44 trillion, the lowest since February 2021, according to the Fed’s weekly balance sheet today. Since the end of QE in April 2022, the Fed has shed $1.53 trillion.

There have been discussions at the Fed about how and when to slow down the pace of QT, the idea being that slowing the liquidity withdrawal will give liquidity time to move to where it’s needed from where it’s in excess, to avoid blowing up something which would then require the Fed to end QT “prematurely,” as they said. “By going slower, you can get farther,” Powell explained during the FOMC press conference.

They’re trying to get the balance sheet down as far as possible, and easy will do it, that’s going to be the program. But not yet.

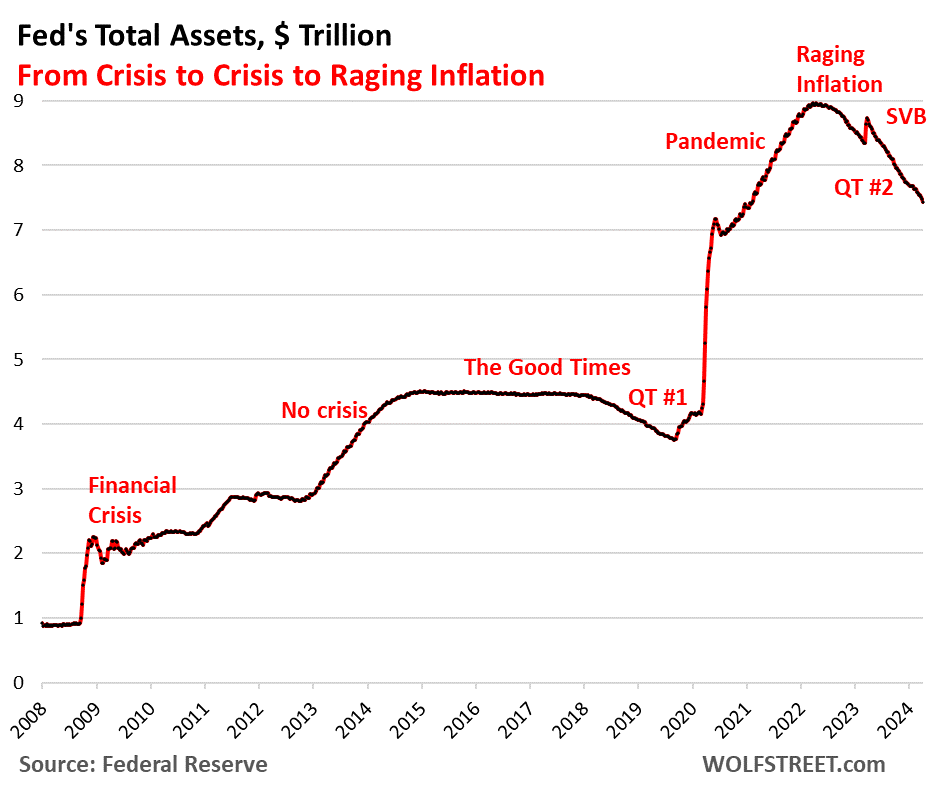

During QT #1 between November 2017 and August 2019, the Fed’s assets dropped by $688 billion, while inflation was below or at the Fed’s target (1.8% core PCE in August 2019), and the Fed was just trying to “normalize” its balance sheet.

Now inflation is above the Fed’s target, though it came down a lot in 2023, and it has started to re-accelerate in a nasty way. Here’s the long view of the Fed’s balance sheet:

QT by category.

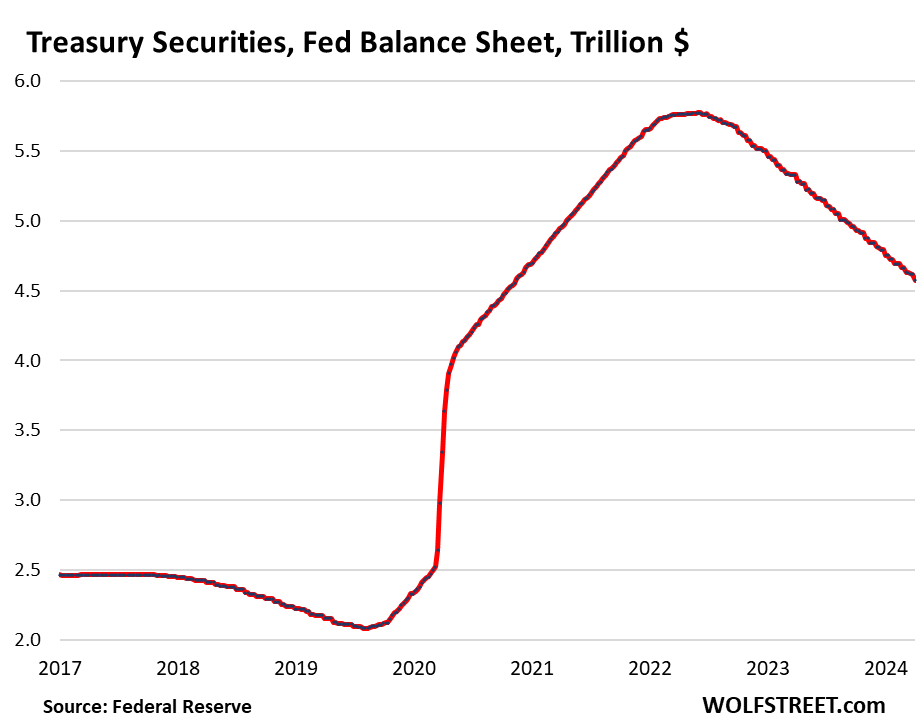

Treasury securities: -$57 billion in March, -$1.20 trillion from peak in June 2022, to $4.58 trillion, the lowest since November 2020.

The Fed has now shed 37% of the $3.27 trillion in Treasury securities that it had added during pandemic QE.

Treasury notes (2- to 10-year securities) and Treasury bonds (20- & 30-year securities) “roll off” the balance sheet mid-month and at the end of the month when they mature and the Fed gets paid face value. The roll-off is capped at $60 billion per month, and about that much has been rolling off, minus the inflation protection the Fed earns on Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) which is added to the principal of the TIPS.

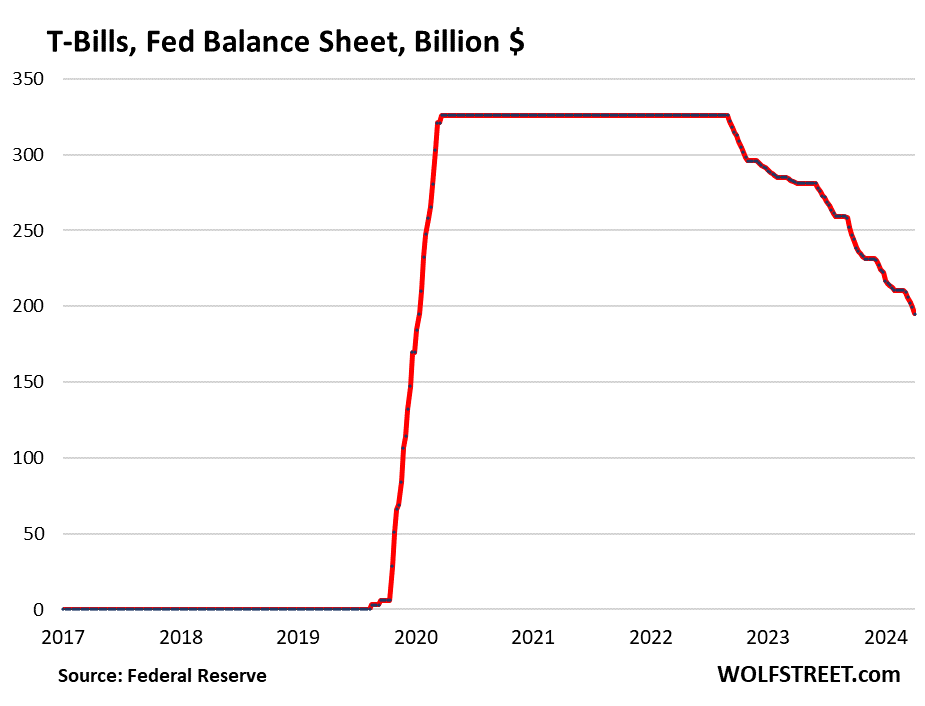

Treasury bills and QT. These short-term securities (1 month to 1 year), now at $195 billion, are included in the $4.58 trillion of Treasury securities on the Fed’s balance sheet.

The Fed lets them roll off (doesn’t replace them when they mature) only if not enough longer-term Treasury securities mature to get to the $60-billion monthly cap. This means that as long as the Fed has T-bills, the roll-off of Treasury securities can reach the cap of $60 billion every month. Here’s the maturity schedule of securities on the balance sheet and for how long T-bills can top off the roll-off before they run out.

From March 2020 through the ramp-up of QT, the Fed held $326 billion in T-bills that it constantly replaced as they matured (flat line in the chart). T-bills started rolling off with QT in September 2022 to bring the Treasury roll-offs to $60 billion a month. They’re now down to $195 billion:

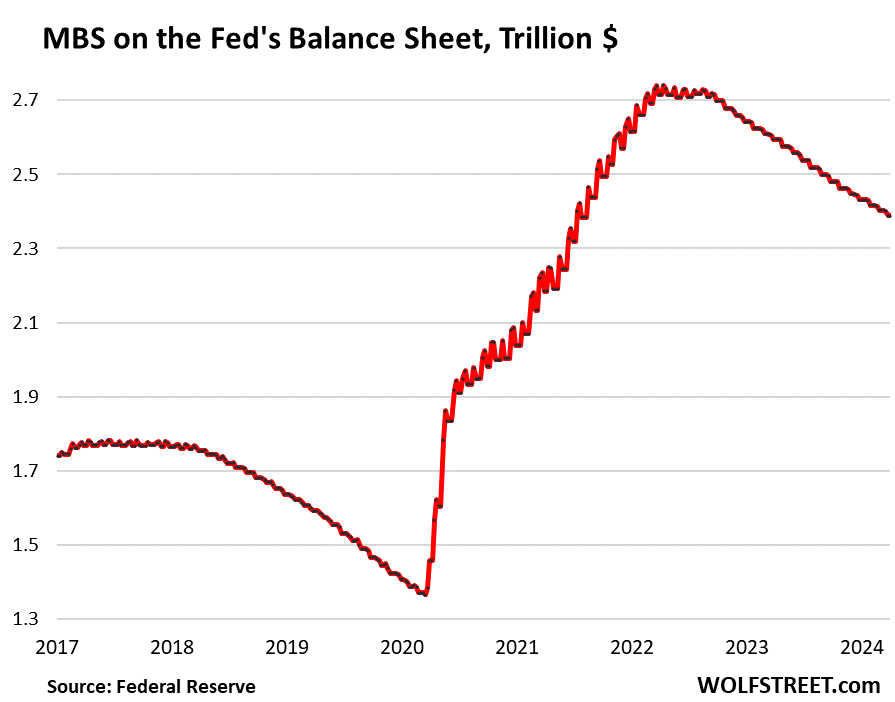

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS): -$15 billion in March, -$352 billion from the peak, to $2.39 trillion, the lowest since July 2021. The Fed has shed 26% of the MBS it had added during pandemic QE.

The Fed only holds government-backed MBS, and taxpayers carry the credit risk. MBS come off the balance sheet primarily via pass-through principal payments that holders receive when mortgages are paid off (mortgaged homes are sold, mortgages are refinanced) and when mortgage payments are made.

But sales of existing homes have plunged, and mortgage refinancing has collapsed, and so fewer mortgages got paid off, and passthrough principal payments to MBS holders, such as the Fed, have been reduced to just a trickle, and so the MBS are coming off the balance sheet at a pace that’s far below the $35-billion cap.

Bank liquidity facilities.

Above we talked about the main elements of QE and QT: Buying and shedding securities for monetary policy purposes. QE and QT are relatively new things in central banking.

Below we’ll talk about liquidity provisions to the banking sector, which is a classic function of the Fed as a lender-of-last-resort to the banks. The Fed has had this function from day one. These measures are not part of QE/QT, but since they have similar effects on the markets, and since they’re on the asset side of the Fed’s balance sheet, we must add them to the discussion.

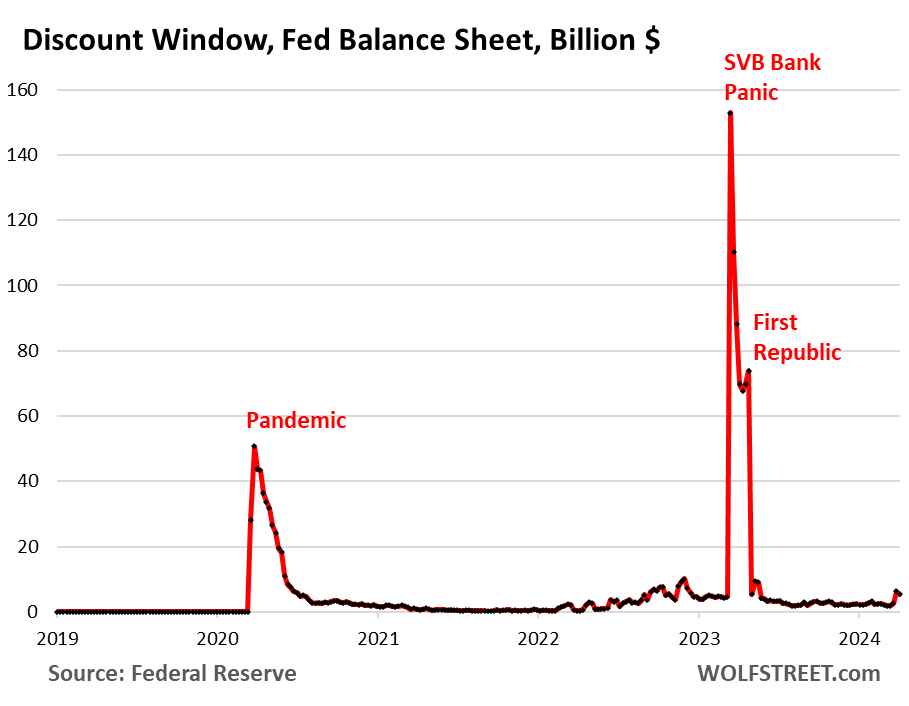

Discount Window: +$3.6 billion in March, to $5.5 billion, but down from $153 billion during the bank panic in March 2023.

The Discount Window is the Fed’s classic liquidity supply to banks. The Fed currently charges banks 5.5% in interest on these loans, and demands collateral at market value, which is expensive money for banks, and so they don’t use this facility unless they need to. The Discount Window rate is one of the five policy rates that the FOMC decides during its policy meetings.

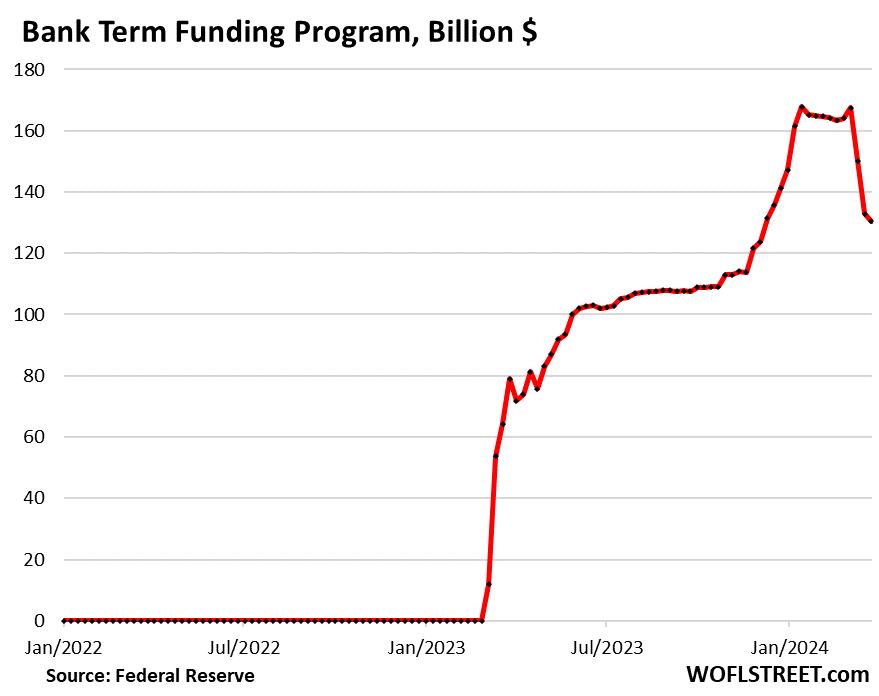

Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP): -$34 billion in March, to $130 billion, and down from the peak of $168 billion.

This thing was cobbled together over the panicky weekend in March 2023 after SVB had failed. It had a fatal flaw that no one thought about at the time. But when rate-cut mania set in November 2023, the fatal flaw became apparent, and some banks used it for arbitrage profits, borrowing at the BTFP at a lower market rate and then leaving the cash at the reserve account at the Fed to earn the higher 5.4% that the Fed is paying on reserves. This arbitrage caused the BTFP balances to spike.

This rankled the Fed to no end, and it shut down the arbitrage opportunity in January by changing the rate, and it let the BTFP expire on March 11. Loans that were taken out before then can still be carried until March 11, 2025, by which time the BTFP will be zero.

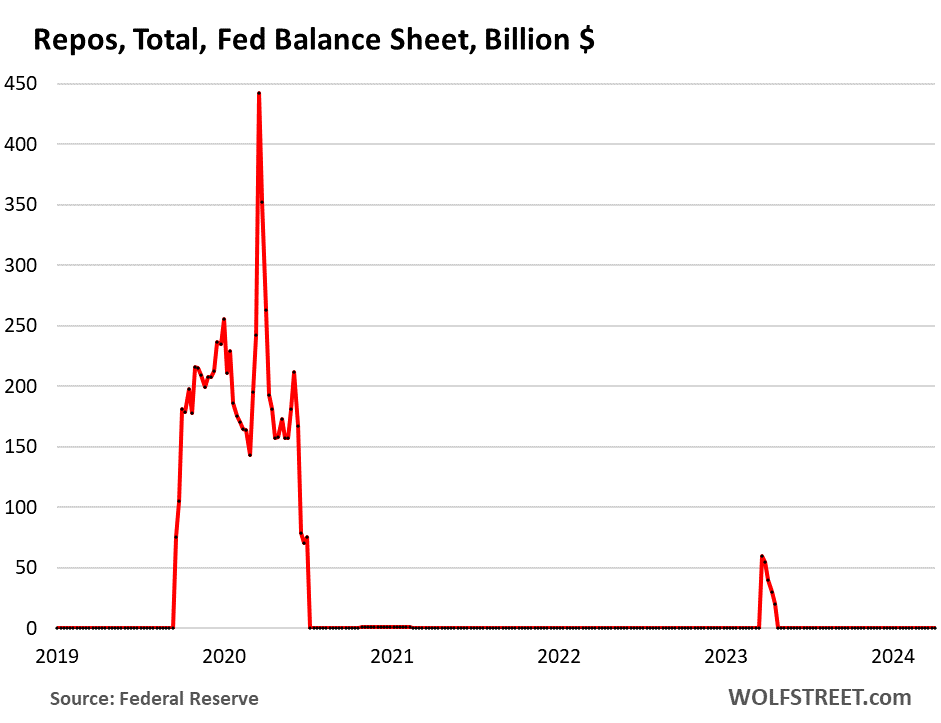

Repos: $0. The Fed currently charges counterparties 5.5% on repos, as part of its five policy rates. The Fed’s repos come in two flavors:

- Repos with “foreign official” counterparties were paid off in April 2023.

- The repos with US counterparties faded out in July 2020 and have remained at around zero.

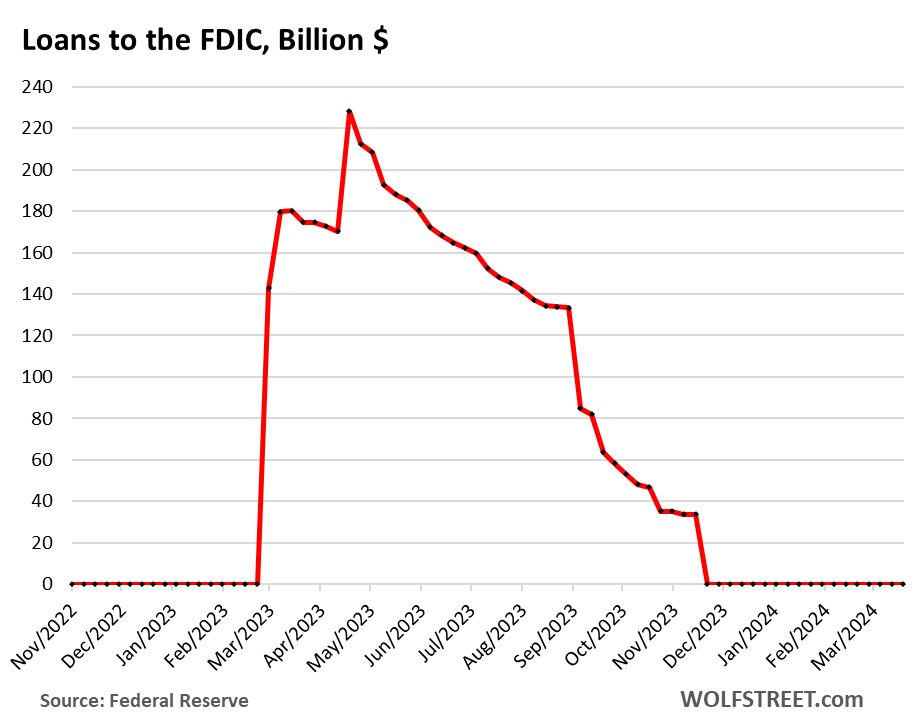

Loans to FDIC: $0. This facility was put together over the bank-panic weekend in March 2023. The funding allowed the FDIC to quickly make whole all depositors – not just the insured depositors – of the failed banks, before it could sell the failed banks’ assets. The FDIC paid off the remainder in November 2023. This is the last time we’ll post the chart here, it has been one year, and it’s over and gone. Good riddance:

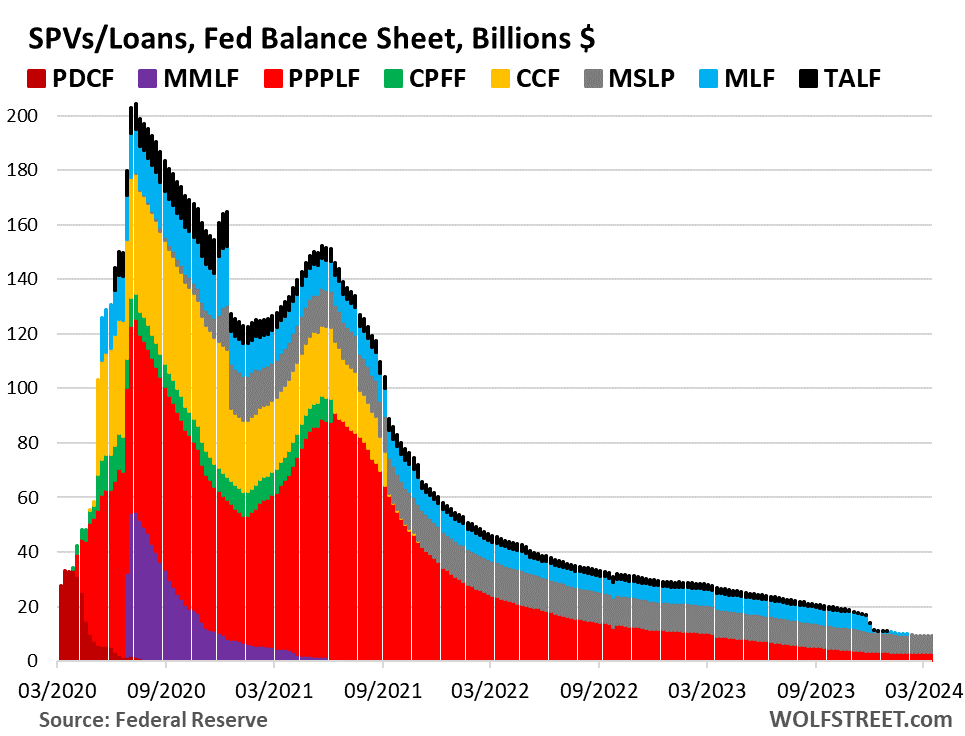

One final word about the pandemic SPVs.

Remember the SPVs, the alphabet soup of seven Special Purpose Vehicles that the Fed had set up during early weeks of the pandemic? We used to have a lot of fun with that stuff here back then. But we haven’t talked about them for a couple of years, so it’s time, one final time.

The purpose was to be able to buy assets that the Fed would not be allowed to buy otherwise. The dodge is simple: it would set up the SPV, lend to the SPV, and it even got the Treasury Department to provide the equity capital, and then the SPV would buy the forbidden assets. In the early months of the pandemic, the Fed then bought those forbidden assets that ranged from junk-bond ETFs to PPP loans.

The first one became active in late March 2020, while the WSJ, Bloomberg, CNBC, et al. ran ridiculous hype-and-hoopla stories of just how many trillions in securities the Fed could buy with these instruments. And it caused markets to rocket higher, knowing that the Fed would buy trillions of dollars of stuff, from junk bonds to old bicycles.

Alas, from get-go it was more of a propaganda coup than anything else. The Fed never bought much. The balances peaked in July 2020 at $205 billion all combined, and then it began unwinding them.

It totally unwound five of the seven SPVs so far, and they’re gone:

- By June 2021, its Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF).

- By July 2021, its Money Market Liquidity Facility (MMLF).

- By November 2021, its Corporate Credit Facility (CCF) which held corporate bonds and bond ETFs, including junk-rated stuff, and it made money on them.

- By January 2024, its Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF).

- By January 2024, its Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF).

Only two stragglers are left, with minimal balances: The Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility (PPPLF) now down to $3 billion from the peak of $91 billion in June 2021; and the Main Street Lending Program (MLF), now down to $6 billion, from the peak of $17 billion in January 2021.

So combined, what’s left of the $204 billion in SPVs is a combined $9 billion. Good riddance.

STAY INFORMED! Receive our Weekly Recap of thought provoking articles, podcasts, and radio delivered to your inbox for FREE! Sign up here for the HoweStreet.com Weekly Recap.

Wolf Richter April 4th, 2024

Posted In: Wolf Street