March 19, 2022 | Lyn Alden: The Russian Impact On Commodities

Excerpted from Lyn Alden’s March 2022 Newsletter:

The global economy, in a blank-sheet-of-paper naïve design that disregards the complicating factors of geopolitics, basically says this: we’ll take Chinese labor and logistics infrastructure, Russian and Brazilian commodities, and developed market institutions and capital, and combine them (and resources from similar countries across the spectrum) into full products and services across the world.

Under this operating framework, we don’t need to build secondary manufacturing and shipping facilities, because we assume the ones we have in China will always be available. We don’t need to build secondary nickel mines for our EV batteries, because we assume the ones in Russia will be open and able to supply the world. Chile can supply our copper, Brazil can supply our soybeans, Russia and Ukraine can supply our wheat, Taiwan can supply our semiconductors, China can supply our labor, and there’s no issue here.

All good, right? For decades yes, until it’s not.

Russia is one of the biggest oil and gas exporters in the world. They’re also one of the biggest exporters of wheat, nickel, fertilizer, platinum group metals, enriched uranium, coal, aluminum, and more. It’s challenging for the global economy to function without those mines, in the event of sanctions. And in most cases, it takes several years to discover and build a new mine, in what is an otherwise tightly-balanced global supply/demand system.

Going forward, any back-tests about inflation or disinflation that only go back twenty or thirty years are practically useless. This whole 1980s-through-2010s disinflationary period (with one substantial cyclical inflationary burst in the 2000s) was during a backdrop of structurally falling interest rates and increasing globalization, with the sacrifice of resiliency for more efficiency.

The world is now looking at the need to duplicate many parts of the supply chain, find and develop potentially redundant sources of commodities, hold higher inventories of everything, and in general boost resilience at the cost of efficiency.

Macro Implications: 2020s vs 1940s

I’ve been making a macroeconomic comparison between the 2020s and the 1940s for nearly two years now, and the similarities unfortunately continue to stack up.

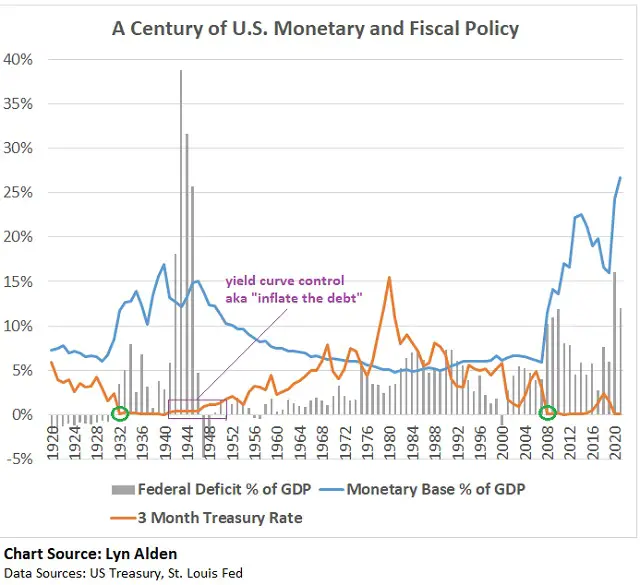

For the most part, I was referring to monetary and fiscal policy and the long-term debt cycle for that comparison, with charts like this that my readers are quite familiar with by now:

I was also referring to social, generational, and institutional cycles, but less so to geopolitics or kinetic warfare. In other words, the 2020s were beginning to exhibit behavior normally associated with wartime finance, but without a war. Instead, it was a massive global fiscal response to a pandemic-related disruption of a highly-levered global economy.

Well, now we can unfortunately throw kinetic war into the mix as well, and then a secondary financial/geopolitical war happening in the background, with frozen sovereign reserves, global sanctions, shifting geopolitical alliances, and so forth. The world, in many ways, is becoming bifurcated or multi-polar. Thousands of Ukrainians are estimated to have been killed or injured in this conflict so far; even if the war ends soon, it will likely have shifted geopolitics for a very long time to come, and in some ways that we may not foresee yet.

At one end, the US and Europe appear more aligned than they have been in a while. At the other end, China and Russia have been pushed closer together, and a number of countries have had to take a neutral stance on Russia’s war with Ukraine due to their economic reliance on Russia.

India, for example, has avoided outright condemning Russia, in part because it is a huge trade partner with Russia (albeit not for oil) and has had a multi-year plan to increase trade with them. India is a big importer of arms and commodities, which are the two export industries that Russia happens to focus on.

Similarly, China gets a considerable amount of energy and commodities from Russia.

South American countries in general have taken a harsher stance on Russia than China or India have, but many of them are reliant on Russia for fertilizer, and have taken steps to avoid fertilizers from being included in sanctioned products.

Egypt has likewise taken a middling stance. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates have also drifted away from the US in terms of relations in recent years, with that trend continuing during this current conflict.

The Wall Street Journal ran a piece called, “If Russian Currency Reserves Aren’t Really Money, the World Is in For a Shock.” The gist of the piece is that if sovereign reserves are easily freezable, this may spur central banks to re-evaluate their reserve practices, and shift more towards gold as a reserve asset once again, while also focusing on maintaining larger raw industrial/agricultural commodity inventories. Scarce commodities, physically held within the country’s jurisdiction, can’t be sanctioned or frozen.

Similarly, Credit Suisse published a piece by former Federal Reserve analyst Zoltan Pozsar, called “Bretton Woods III” with this rather strong introduction:

We are witnessing the birth of Bretton Woods III – a new world (monetary) order centered around commodity-based currencies in the East that will likely weaken the Eurodollar system and also contribute to inflationary forces in the West.

A crisis is unfolding. A crisis of commodities. Commodities are collateral, and collateral is money, and this crisis is about the rising allure of outside money over inside money. Bretton Woods II was built on inside money, and its foundations crumbled a week ago when the G7 seized Russia’s FX reserves…

Read the rest of Lyn Alden’s newsletter here.

STAY INFORMED! Receive our Weekly Recap of thought provoking articles, podcasts, and radio delivered to your inbox for FREE! Sign up here for the HoweStreet.com Weekly Recap.

John Rubino March 19th, 2022

Posted In: John Rubino Substack

Next: Just a Bear Rally? »