July 27, 2025 | Uncertainty Squared

Many people yearn for a simpler life. Ironically, that’s the one thing we’re almost guaranteed not to get. Technology keeps shifting the ground beneath us, mostly for the better, but also creates complications for businesses and individuals. The rules, especially from the government, seem to keep shifting, too. Everything around us just gets more and more complicated, including the economy and markets.

In last week’s Inflationary Confusion letter I tried to show the difficulty of knowing which way inflation and interest rates will go. It’s not that we lack evidence. We have too much evidence, to the point you can find convincing reasons to believe pretty much anything. Then confirmation bias takes over, and people feel sure whatever they want to happen is going to happen.

It gets worse. Those who desire a certain outcome tend to cluster together, convincing each other this thing they want will occur, especially if they all just believe it fervently enough. Sadly, that’s not how it works. Our desires don’t define the future.

The answer sounds simple but is fiendishly hard: Admit you don’t know what’s coming. Recognize the many possibilities—including the possibility you don’t know what you don’t know. Then examine all the scenarios you can imagine, assign probabilities to each one, design a strategy to fit the most likely, and have the ability to adapt if things change. This is called “analysis” and it’s a lot harder than it sounds.

Today I’ll continue talking about uncertainty. I want to highlight the complexity we face and also describe the jarring surprise some of us feel when our most trusted sources say things we didn’t expect… and the importance of listening to them anyway.

Collective Thinking

Perhaps the most confusing part of all this is how markets react to what seems like bad news. We have many precedents for what high import tariffs can do to an economy. I can find no precedents which are good.

US financial markets, especially the bond market, seemed to know this back in April, when they reacted correctly by selling off. Now the opposite is happening, even though the basic facts haven’t changed. What is going on?

First, let’s remember a trite but true saying: Bull markets climb a wall of worry. Bullish investors—or at least some of them—aren’t oblivious. They see the same data as bears do but conclude stock prices can keep going up. Indeed, the presence of bears helps the bull keep charging.

Another trite saying? In any market, there is a seller for every buyer and a buyer for every seller, and agreed-upon prices. Bull markets develop when there are more who want to be buyers than sellers. But bear markets are not created by sellers, but simply by an absence of buying. Those market conditions can last for a very short time or go on for a decade.

This thing we call “the market” is the collective result of millions of investors trying to predict the future. It reflects what they think is coming.

I know very few bullish investors who think tariffs are good. Mostly, they see tariffs as the “least bad” response to an intolerable situation. They recognize the ill effects but believe the tariff pain will end soon. (More on that below.) In this view, the current confusion and chaos will lead to a new equilibrium that is manageable and maybe even positive. They don’t think it will be bad enough to derail the other bullish factors like AI technology.

If that’s what you believe, then it makes sense to take advantage of current bearishness to buy more. I’m not in that group but I understand their thinking. What I don’t see is reason to think the tariffs lead to even a neutral outcome, much less a good one. I’ve gone over the reasons before and won’t repeat them now. (Read this if you’re interested. It is my letter from April 25 and realize how much change there has been since then. Rather astonishing, really.)

The best case I can imagine is that tariffs will raise import prices for American consumers enough to show up as higher inflation but not enough to trigger a recession. Because I think even 2% inflation is too high and robs all of us, I don’t see that as a good trade-off. Further, the way all this is being done makes the hoped-for manufacturing revival more difficult in reality than it is in the theory that some political types believe.

I would also note that bulls keep moving the goal posts. Stocks rallied back from their April crash because Trump postponed the highest tariff rates for 90 days, during which he was going to negotiate a bunch of great deals with our top trading partners. The 90 days passed with no significant deals.

Now we are told higher rates are coming in August, but traders seem to think those rates won’t happen, either. Maybe they’re right. But other governments are planning their retaliatory moves, and this could easily spiral into a broader trade war. Hopefully cooler heads will prevail, and we won’t end up with a repeat of the spiraling Smoot-Hawley tariffs.

I get the idea of “seeing through” short-term volatility. My problem is with the “short-term” part. I just don’t see the finish line. I assume one is out there. I don’t think it is near.

Thoughts on Tariffs and Inflation

I had a few readers ask why taxes like import tariffs will cause inflation as income taxes don’t. Tariffs are essentially a consumption tax. As an example, when Japan raised its sales tax from 5% to 8% in April 2014, consumer prices rose by 3.2% compared to the previous year, marking the fastest increase in 23 years. That Japanese tax hike was part of a broader effort to combat deflation and stimulate the economy, but it also led to a decline in household spending shortly after the increase.

Here’s where it gets a little tricky for those not familiar with how inflation is measured. That Japanese sales tax was a one-time increase in the price of goods. Typically, countries measure inflation over a period of 12 months. Let’s say the price of rice went from ¥100 to ¥103 thirteen months later. That sales tax was already included in the price. If market conditions didn’t change, there would be 0% inflation on rice the next year, even though the actual price was still ¥103. Even though 3% inflation is now built into the statistics, it still changes the mix of goods and services that a consumer on a generally fixed level of income will buy.

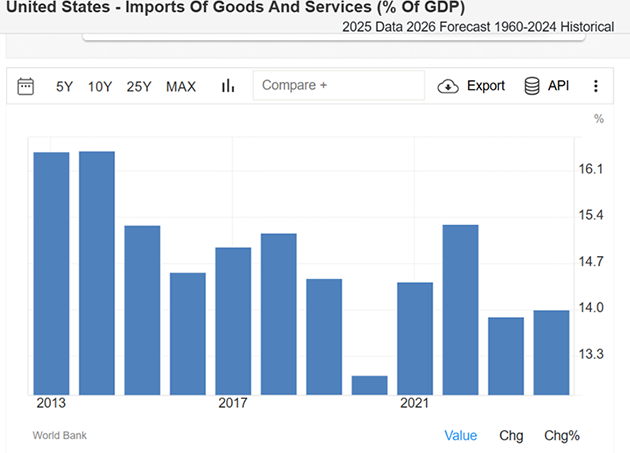

Tariffs have the same effect. Once we get finality on the actual tariffs, it will be a one-time increase. Imports were 13.99% of the US economy in 2024, although you can see that number fluctuates.

Source: Trading Economics

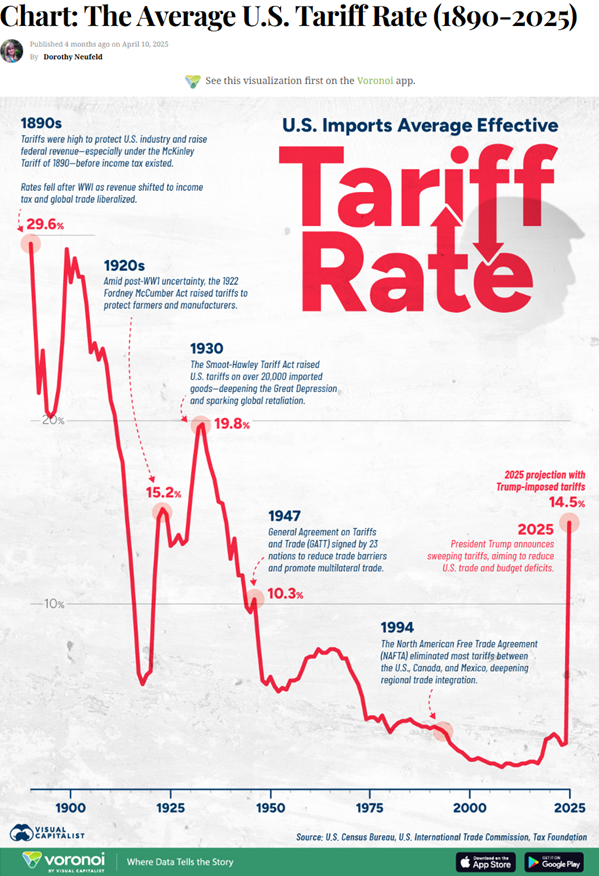

The average tariff rate is now roughly 14% but is clearly headed higher than we’ve seen for a very long time.

Source: Visual Capitalist

In 2024, the total value of US imported goods and services amounted to approximately $4.1 trillion. Not all of those goods and services will have a 14% tariff rate. US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent claims tariffs will produce $300 billion in revenue in 2025. That will likely rise in future years. Given extreme government deficits, we need that revenue, although I would like to see it in a different form.

Since we don’t know what the final tariffs will look like, estimates of total revenue are all over the board. There are numerous estimates in the $3 trillion range for the next 10 years and some as high as $4+ trillion. CBO calculates that tariffs will increase inflation by 0.4%. That will make the life of some future Fed chair very difficult.

Let’s assume markets are right and we get two rate cuts this year. Even if service inflation (mostly housing) continues to fall, inflation might still be above the 2% target in the first part of next year. Over time that impact goes away but what do you do in the meantime as you try to find the appropriate level of interest rates?

President Trump wants the fed funds rate to be 1% so that the Treasury could pay less interest and have a lower deficit. Of course, that would punish savers and retirees and distort the economy in new and different ways. Should we have lower rates? I think the answer is yes, but slowly and with a very careful eye on inflation.

I am puzzled as to why anyone would want to be the Federal Reserve chair in such an environment.

Front Running

Speaking of uncertainty, last week KPMG Chief Economist Diane Swonk posted an X thread on what she called “the mother of all front-running cycles.” She somehow manages to describe the current situation both succinctly and comprehensively, a skill that eludes many economists.

The pic is the first of a whole series of posts. I’ve combined them with some minor edits below, as I think Diane brings up some very important points:

“Late last year imports started to pick up, notably from China. The 2018 Trump tariffs had mostly continued through the Biden administration, but many firms rightly bet they would escalate via much higher tariffs with the president’s return.

“Then, those gains were turbocharged as tariff threats intensified in the first quarter. Imports soared in what could best be termed as the mother of all front-running cycles. They hit a crescendo in March.

“Those increases buoyed production across our trading partners. Our trade deficit widened at its fastest pace on record, by nearly double.

“At the same time, the consumer became tentative and consumer spending all but froze along with the housing market. Consumer spending rose a tepid 0.5% annualized rate in the first quarter after surging 4% in the fourth. Some of that weakness was due to a late Easter and uneven spring breaks. Unusually cold weather in the South curbed mobility and spending, notably at restaurants.

“Then came the announcements of April 2. That roiled markets and imports collapsed. The trade deficit narrowed at its fastest pace on record in April and in May, imports from China dropped to their lowest share of total imports since 2001. That is the year of their ascent into WTO.

“Earlier gains boosted production the world over—Ireland saw a 7% surge in GDP due to a huge jump in pharmaceutical exports to the US—tariffs on those have gotten a stay but we now have a lot of drugs in inventory.

“Consumers here regained some but not all of their swagger. The rebound in equity prices helped, especially in an economy where Moody’s has estimated that the top 10% of earners accounted for nearly half of consumer spending last year. It looks like spending increased by around a 1.4% rate. That is still weak but better. June retail sales rebounded after falling in May.

“Problem: Inequality has a lot of knock-on effects. High-income households have their basic needs met. They save and make riskier investments than other households.

“At the same time, strapped low and middle income households tend to take on unsustainable levels of debt, which at times can seem like a boom to lenders, until it isn’t and defaults pick up. Delinquencies are still low in the wake of pandemic stimulus but rising…

“High-income households with more savings tend to make riskier investments as they can afford the losses. That makes for fertile ground for asset bubbles. An extreme example was the subprime crisis, which ended with the bursting of the housing bubble and ripple effects. I don’t know all the places that bubbles are forming but a lot of asset prices look frothy.

“Now add another issue. The economic data isn’t designed to capture the speed of the shifts we are seeing. A lot of inputs are estimated off of historic trends and then updated upon revision. At the same time, budget cuts are crimping data collection, which means more estimates are based on history or imperfect substitutes.

“Nearly 1/3 of the CPI in recent months has been estimated via these methods, which would be fine if the shifts we were seeing were not so rapid. It is unclear how/if those estimates changed the data.

“We know front-running mitigated the initial boost to prices due to tariffs. Much of the goods that we bought in the second quarter were bought by retailers ahead of tariffs. Some retailers actually dropped prices as they ran those inventories down and shored up cash flow. Much of what we are seeing on store shelves still reflects a pre-tariff world.

“This at the same time that firms are actively mitigating the effects of tariffs by reshuffling supply chains and increasing the certification of parts that qualify for lower tariffs.

“Another factor preserving cash flow is bonded warehouses in free trade zones in the US. Goods come in and are registered as imports, but tariffs are not collected until those inventories are withdrawn and drained. The cost of carrying inventories is not cheap but it is less expensive in many cases than fronting the funds for tariffs before goods are needed. They enable firms to wait for tariffs to drop, which occurred as many of the most prohibitive tariffs were paused.

“The result is a much smaller initial impact of tariffs and stronger global growth than one would expect. Disinflation abroad has also helped as most major central banks have been cutting rates, the effects of which are compounding.

“Bottom line: Tariffs are distorting the global economy, but the effects are nonlinear and compound over time. We will not know all of the effects until later this year and into 2026. It took years for the full effects of the 2018 trade war to show up as a blow to manufacturing.”

I agree with Diane on that last part. Thanks to front-running, inventory build, and the other factors she outlines, the full impact tariffs (and threats thereof) will ultimately have is not yet visible. That doesn’t mean it will be minor.

Keep in mind, also, the “waiting for resolution” itself has a cost. Businesses are delaying decisions or making unwise decisions because so much is still unknown.

If (hypothetically) Trump had announced new tariff rates and stuck with them, the economy would take a hit but then adjust. Instead, we have this paralyzing uncertainty. The effects are hard to measure but definitely real.

“The Only Viable Tool”

Long-time readers know of my deep respect and deep personal affection for Dr. Lacy Hunt. He’s someone of both bottomless economic knowledge and the highest personal integrity. He routinely challenges my beliefs and helps me look at the economy in new ways. His latest quarterly report definitely did it again.

Lacy’s headline wasn’t surprising: Tariffs—A Race to the Bottom, Why Take the Risks? He proceeded to deliver a strong argument, with plenty of evidence, describing the economic damage tariffs typically cause. It was exactly what you would expect from a zealous free market advocate.

It thus came as a shock to turn the page and see Lacy saying tariffs are… necessary anyway, despite all the reasons he had just given for their being a bad idea.

I don’t want to get this wrong, so I will quote that whole section verbatim.

“Why Take the Risk of Raising Tariffs?

“In addition to the risk of boosting tariffs previously discussed, another consideration for many is David Ricardo’s ‘law of comparative advantage,’ which is the benefit accruing to all countries that engage in international trade, even if a country does not have the lowest total cost of producing a good.

“However, for this benefit to work, all countries engaging in trade must allow Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ to prevail. But the world has many mercantilists, some of whose practices result in massive intrusions on the ‘invisible hand,’ which, in turn, have hollowed out the US industrial base to the benefit of other countries.

“As demonstrated by the supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine War, the US experienced severe shortages of drugs, medical equipment, and a host of other products that could not be produced domestically. Command and control dominate free markets in these mercantilist economies. Thus, by hollowing out the US industrial base, the world’s resources are being more inefficiently distributed, and thereby reducing the capacity of the global economy to raise its standard of living.

“Since negotiations have consistently failed to reverse this situation, tariffs, despite their negative effects, remain the only viable tool to create a more strategically diversified industrial economy and to move the world back toward a more efficient allocation of its resources.”

You have to know Lacy to realize what a thunderbolt this was. He is in no way a fan of taxes or government intervention. Quite the opposite. I knew instantly he hadn’t reached this conclusion without a lot of thought.

(I should note that while I’ve sometimes talked with Lacy about his letters as he writes, I read this one cold. We didn’t discuss it beforehand, and I had no idea he was going to say this.)

I was travelling this week and unable to talk with Lacy, so I’ll defer specific comments for now. But I’ll say this: We know we’re in truly extraordinary times when the most intelligent among us say such surprising things. We should see it as an opportunity to rethink our own assumptions and preconceptions. If our beliefs are right, they will withstand scrutiny. If they’re wrong, we have an opportunity to change them.

It just adds to the uncertainty that we collectively experience, as changing our minds is its own special form of uncertainty.

Newport Beach, Dallas, and British Columbia

I will be heading to Newport Beach to meet with David Bahnsen, Brian Szytel, and their team at The Bahnsen Group the second week of August. We will be doing some videos and meeting with potential TBG clients in the area.

There is no date set yet, but I will likely have to be in Dallas sometime in August. Then at the end of the month, Shane and I will be meeting 33 other friends and readers at the West Coast Fishing Club in far northwest British Columbia trying to find a few hopefully trophy salmon, halibut, and Ling cod (my vote for the ugliest fish with the best taste). It is a true five-star fishing resort on a remote island. You are so far north that when you are out on the water you can see Alaska. I am really looking forward to it.

New York was very productive, both business and personal. I met with my Mauldin Economics partners Ed D’Agostino and Olivier Garret. We have some exciting plans for this fall that will help you in both your professional and personal lives. Dinner with them and friends Peter Boockvar, Ben Hunt, and Steve Blumenthal made for a fabulous evening.

The next night I met with David Bahnsen, his partner Brian Szytel, and Renè Aninao. It is hard to describe just how wired David and Renè are into the deep inner circles of government and politics. Listening to them analyze current events and people is just amazing. A lot of our conversation was clearly off the record, or I would simply record and transcribe it for you. It becomes background information for me. I find my time with them to be some of the most useful and personally satisfying experiences every time we are together. We have developed a deep friendship over the years.

As I have with so many. I am one of the luckiest guys I know to have so many great friends. And Shane on top of that. And with that, it is time to hit the send button. I think I’m going to spend a few hours this weekend just calling friends and catching up. You have a great weekend!

Your certain about the value of friendships analyst,

John Mauldin

STAY INFORMED! Receive our Weekly Recap of thought provoking articles, podcasts, and radio delivered to your inbox for FREE! Sign up here for the HoweStreet.com Weekly Recap.

John Mauldin July 27th, 2025

Posted In: Thoughts from the Front Line

Next: The Schema Frequency »