The Canadian unemployment rate rose to 6.9% in April (from 6.7% in March). Outside of the 2020 COVID shutdown, this was the highest level since January 2017 and up 210 basis points from the July 2022 cycle low of 4.8%.

This is a warning sign: in past cycles since 1953, we have been six months into a recession by the time the unemployment rate has risen 101 basis points (1.1%).

The national election on April 28th helped drive a temporary surge in public administration employment (+37k), which offset a 31k loss of manufacturing jobs. Ontario bore the brunt of the weakness with employment down 35k in April and -50k since February, while the unemployment rate rose to 7.8%–the highest in nearly four years.

In its recently released Monetary Policy Report for April 2025, the Bank of Canada noted two potential scenarios unfolding.

Scenario 1, where new tariffs are negotiated away, but the process is unpredictable and continues to spook businesses and households. In that case, they see: “GDP growth in this scenario stalls in the second quarter, then expands only moderately. Inflation drops below the 2% target for the rest of 2025 and into 2026, because of the end of the consumer carbon tax and a weak economy.”

In Scenario 2, a long-lasting global trade war causes Canada’s GDP to contract in the second quarter, and the economy goes into recession for a year. In this case, they assume growth gradually returns in 2026 but remains soft through 2027 as US tariffs permanently reduce Canada’s potential output and lower our standard of living: “Inflation rises above 3% in mid-2026 as tariffs, countermeasures, and shifts in supply chains raise costs, pushing up many prices. Inflation then eases as weak demand limits ongoing inflationary pressures”.

The Governing Council agreed that the April 2 US trade announcement would put the situation closer to Scenario 2. However, the partial rollback on April 9 and new exemptions since have potentially moved trade policy back towards the middle of the two scenarios.

As I have noted for some time, the Bank of Canada’s relatively sanguine outlook for the Canadian economy over the past couple of years was predicated on the assumption that employment would remain strong and households would remain current on their debt payments. Those assumptions are increasingly in doubt.

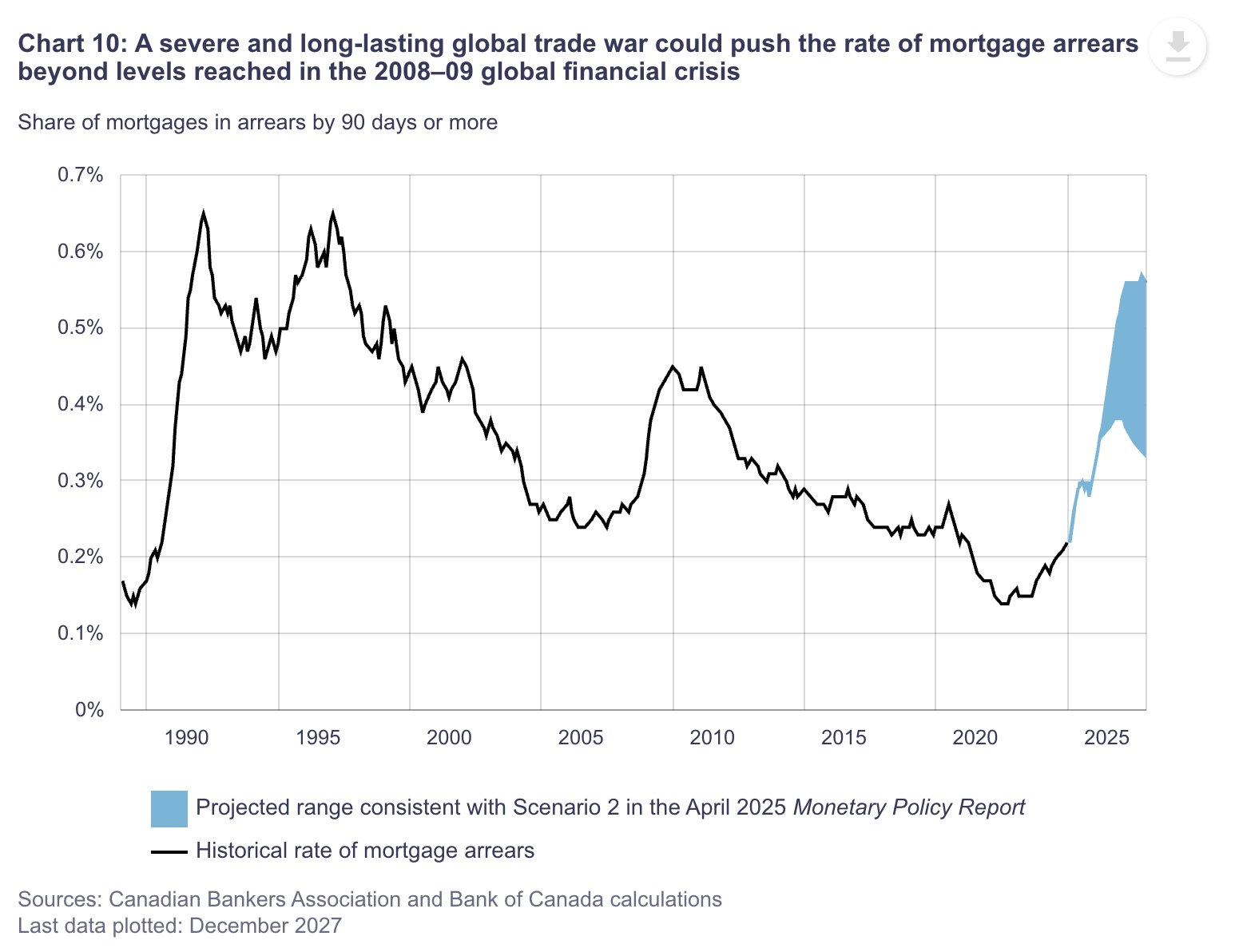

A scenario-two long-lasting trade war would raise the rate of mortgage delinquencies above the rates seen during the 2008 financial crisis (shown in blue below since the late 1980s).

This suggests further pain for borrowers and lenders, home prices, and Canada’s highly leveraged, real estate-sensitive economy. The case for capital protection has rarely been greater than now.

This suggests further pain for borrowers and lenders, home prices, and Canada’s highly leveraged, real estate-sensitive economy. The case for capital protection has rarely been greater than now.