July 10, 2025 | A Closer Look At Germany’s Death Spiral

Subscriber Bill G responded to yesterday’s post on Germany’s financial/cultural death spiral by asking:

“And when did debt to GDP cease to be a good measure of economic health? https://countryeconomy.com/countries/compare/germany/usa?sc=XE02”

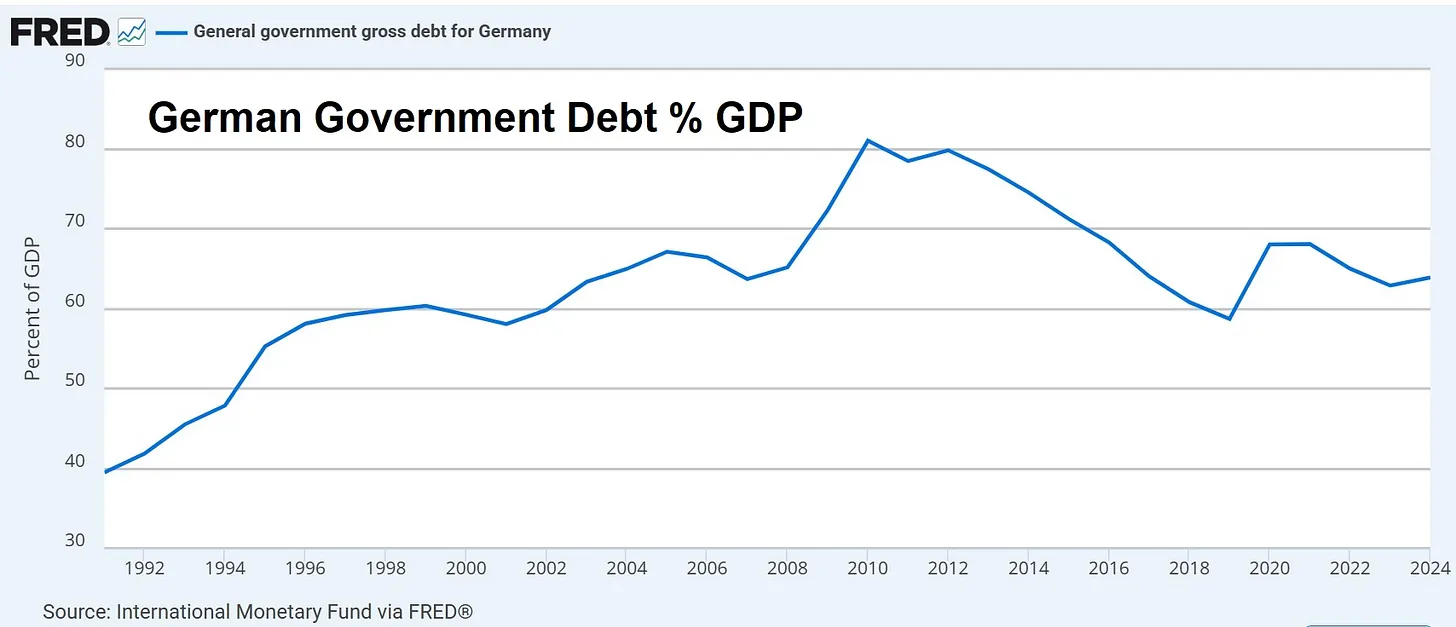

His point is that if Germany’s government debt is only 65% of GDP, that country is — by definition— in way better shape than the US (debt 120% of GDP).

This is a reasonable question with an interesting answer. So here goes:

Vendor Financing

In the business world, there’s a semi-sleazy practice in which a company lends money to its customers who then use that money to buy the company’s products. This boosts sales and profits, making company managers seem worthy of big year-end bonuses.

Assuming the debtor/customers can pay off their loans, this practice can continue, unbeknownst to outsiders, for a long time. But if customers start defaulting, the “vendor financing” scheme unravels.

Germany has been running the government version of this scam.

With the introduction of the euro as a common currency in 1999, it became clear that eurozone members had wildly differing financial profiles. Greece and Italy, for instance, were bankruptcy candidates who, in a rational world, would have to pay way up to borrow money. But high interest rates would render their debt prohibitively expensive, forcing them out of the eurozone.

So the currency union cooked up the following scheme: The European Central Bank (ECB) would buy non-German government bonds at prices that equated to extremely low interest rates. And Germany would guarantee the solvency of the ECB.

For long stretches, most eurozone countries were able to borrow at lower rates than the US government had to pay, since their bonds were de facto German (i.e., “investment-grade”) paper.

Now here’s where “vendor financing” comes in. Italy, Greece, Spain, et al used some of the money they borrowed to buy German-manufactured goods. As a result, Germany’s economy grew, its trade balance was positive, and its government deficits were modest (when they weren’t actual surpluses).

It’s easy to view the resulting chart as a picture of a financially sound entity.

But remember that Germany, via the ECB, had promised to make good on everyone else’s bonds. Should, say, Italy default, those obligations would in effect become part of Germany’s national debt. So its real obligations are much higher than the official numbers.

And now that Germany is “deindustrializing,” its ability and willingness to cover everyone else’s debts are being called into question, causing peripheral Europe’s interest rates to rise. Note that Spain was able to borrow 10-year money for less than 2% until 2022, when the US ended Germany’s cheap-energy industrial preeminence by blowing up the Nord Stream gas pipeline.

A Eurozone Without Germany Is Toast

So here we are, at a crossroads: Either peripheral Europe starts paying market rates for its ever-increasing government debt, which will force the dissolution of the eurozone and a return to national currencies. Or the ECB — without explicit German guarantees — steps back in and buys huge amounts of low-quality sovereign debt with newly created currency, which will spike inflation and crash the euro.

Either way, Germany’s days as an industrial powerhouse are over, and the eurozone is, as a result, toast.

STAY INFORMED! Receive our Weekly Recap of thought provoking articles, podcasts, and radio delivered to your inbox for FREE! Sign up here for the HoweStreet.com Weekly Recap.

John Rubino July 10th, 2025

Posted In: John Rubino Substack

Next: Market Pulse – July 10/25 »