December 15, 2025 | Compound Interest Is Devouring the Federal Budget: It’s Time to Take Back the Money Power

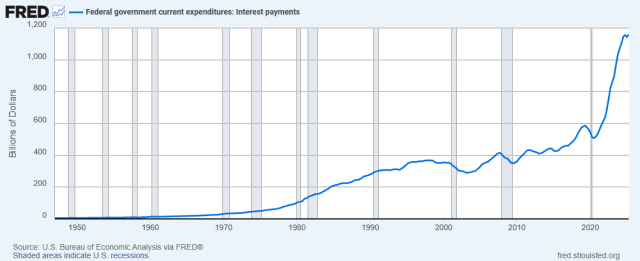

Albert Einstein is often quoted as saying that compound interest is “the most powerful force in the universe.” The quote is probably apocryphal, but it reflects a mathematical truth. Interest on earlier interest grows exponentially, outrunning the linear growth of revenue and eventually consuming everything.

That is where the United States now stands. The government does pay the interest on its debt every year, but it is having to pay it with borrowed money. The interest curve is rising exponentially, while the tax base is not.

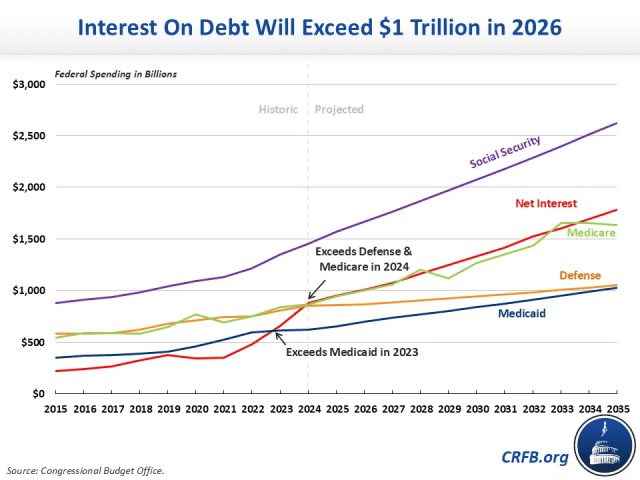

Interest is now the fastest growing line item in the entire federal budget. The government paid $970 billion in net interest in FY2025, more than the Pentagon budget and rapidly closing in on Social Security. It already exceeds spending on Medicare and national defense and is second only to Social Security. The Congressional Budget Office projects that interest will reach nearly $1.8 trillion by 2035 and will cost taxpayers $13.8 trillion over the next decade. That is roughly what Social Security will pay out over the same decade (about $1.6 trillion a year). The Social Security Trust Fund is running dry, not because there are too many seniors, but because interest payments are consuming the federal budget that should be shoring it up.

Critics accuse the U.S. of “printing dollars” and exporting inflation, but it is not the government that is printing these dollars. Most of the money supply in modern economies consists of deposits created by private banks when they make loans.

Meanwhile, the producing economy is suffocating. The money supply (M2) has not shrunk, but it is largely trapped in reserves, financial assets and corporate balance sheets. Households are short of cash, wages are too low and demand is suppressed. What the real economy needs is liquidity directed to productivity, not locked in speculative pools.

However, every year more of the nation’s income is diverted to bondholders instead of workers, infrastructure or production. This is not “borrowing from the future.” It is tribute — a structural transfer of public wealth to private creditors for the use of our own money — money that is legally backed by the full faith and credit of the American people and could and should be created by our representative government.

Why the Usual Solutions Can’t Stop the Interest Spiral

As the debt burden grows, policymakers are floating a variety of proposals. But none of them addresses the structural problem: the exponentially growing interest on the debt.

1. Quantitative Easing (QE)

Some analysts argue that the Federal Reserve will soon be forced back into QE, injecting reserves into banks by buying Treasuries. But even if the Fed bought the entire debt tomorrow, taxpayers would still owe the same trillion dollar interest bill. The payments would simply shift from pension funds and foreign central banks to commercial banks.

The Fed is required to remit its profits to the Treasury after deducting its costs. But since 2008, it has paid interest on bank reserves held at the Fed (IORB). That tab now runs at more than $100 billion annually and is consuming the Fed’s profits, which the Fed pays to banks instead of remitting them to the Treasury. (For a fuller explanation, see my earlier article here.) When bonds are transferred to the Fed through QE, the debt service remains; only the postal address changes where the checks are mailed.

2. Stablecoins

Pegging government liabilities to crypto tokens also does not eliminate interest costs. Stablecoins merely replace lost creditors with new ones. The government still pays the interest — only to a different set of holders.

3. Gold Revaluation

Fort Knox holds about 147 million ounces of gold. At statutory book value ($42/oz), it is recorded at about $6 billion; at current market prices (around $4,000/oz), it would be worth roughly $589 billion. That’s a dramatic increase, but it covers less than a single year of interest payments. Gold revaluation generates too little to fix the problem.

4. Asset Sales

Selling federal land or auctioning off slices of the public airwaves to private carriers can generate one-off proceeds but not recurring flows. They too cannot sustainably cover annual interest obligations.

5. Austerity and Tax Hikes

Austerity shrinks GDP and worsens the debt to GDP ratio, and tax hikes cannot keep up with exponential interest growth.

Restoring the Treasury’s Sovereign Money-Creating Power

It may be time to reconsider a proposal made in the early 1980s, when the idea of minting some large denomination coins to solve economic problems was suggested by a chairman of the Coinage Subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives. He pointed out that the government could pay off its entire debt with some billion-dollar coins. The Constitution gives Congress the power “to coin money [and] regulate the value thereof,” and it places no limit on the value of the coins it creates.

Capitalizing on the seigniorage from minting coins — the difference between their production costs and face value — is now done routinely by the Treasury. When the Mint produces a quarter, the Fed buys it at face value ($.25), even though it costs only about $.12 to make – a 100% profit. This just needs to be done in much larger numbers.

In legislation initiated in 1982, Congress imposed limits on the amounts and denominations of most coins. The one exception was the platinum coin, which a special provision allowed to be minted in any amount for commemorative purposes.

In 2013, with the endless gridlock in Congress over the debt ceiling, the idea was proposed to capitalize on this loophole and mint some trillion-dollar platinum coins. Philip Diehl, former head of the US Mint and co-author of the platinum coin law, confirmed that the coin would be legal tender. He stated, “In minting the $1 trillion platinum coin, the Treasury Secretary would be exercising authority which Congress has granted routinely for more than 220 years . . . under power expressly granted to Congress in the Constitution (Article 1, Section 8).”

Modern Monetary Theory economists, including Warren Mosler and Prof. Randall Wray, showed that the coin would work operationally: it would be deposited at the Fed, crediting the Treasury’s account without circulating in the consumer economy. Spending would still require Congressional approval, but financing would no longer depend on bond markets.

But the coin was dismissed as a gimmick, and the debt ceiling crisis was resolved by simply raising the ceiling. Today, however, with compound interest threatening to devour the entire budget, that solution won’t work. It’s time to look again at a financial innovation employed by our founding fathers to win the American Revolution and the Civil War — government-issued money.

Remembering Our Roots

The battle over who has the privilege of creating the money supply — government or banks — has raged for centuries. Today, private banks have won that battle. But it hasn’t always been this way.

Benjamin Franklin was called “the Father of Paper Money.” He argued before the British Parliament that government issued money had allowed the colonies to escape the burden of debt, to thrive and grow. The king, urged by the Bank of England, responded by forbidding all new issues of paper scrip. The colonial economy then sank into a depression, and the colonists rebelled. They won the revolution, but the power to create money for which they had fought was lost to a private banking oligarchy modeled on the one dominated by the Bank of England.

In 1862, President Lincoln boldly took back the money power during the Civil War. To avoid exorbitant interest rates on loans from British backed bankers of 24% to 36%, he had the U.S. Treasury print money directly as U.S. Notes or “Greenbacks,” nearly doubling the money supply. The Greenbacks were key to funding not only the Union’s victory in the war but an array of pivotal infrastructure projects, including a transcontinental railway system, land-grant colleges, and the homestead system. Prices did go up, but it was due to a lack of supply rather than increased demand, as the production of consumer goods was diverted to war.

Unfortunately, Lincoln was assassinated, and the Greenback program was quickly discontinued. Repeated popular attempts to revive it failed. Coins were the backbone of the money supply when the country was founded, but they shrank in significance over the nineteenth century, as bank-created deposits backed by loans grew in importance. By the time modern monetary statistics were available, physical currency had become a minor part of the money supply, and today coins are only a tiny percentage of it.

Enter the Federal Reserve: Who Does the Central Bank Serve?

In an April 2025 essay titled “How Private Banking Replaced Public Money,” economist Michael Hudson wrote, “Money has always been a product of the government, but in the late 19th century, banking began to be thoroughly privatized and taken out of the hands of any government that controlled it.” The 1913 Federal Reserve Act entrenched this privatization, aligning monetary power with banks rather than democratic government. In a Sept. 2022 interview on The Ralph Nader Radio Hour, Hudson argued:

It was the Treasury that organized the internal improvements for America – the Erie Canal, the roads, all of the spending into the economy. And the Federal Reserve was created to stop social purpose spending by the government, by essentially cutting the Treasury out of the monetary management process. … The role of central banks is to prevent the government from spending money on social programs and to support the commercial banks in lending money to inflate the asset markets – real estate primarily, also stocks and bonds to support private raids of corporations. And essentially, because their product is debt, to load the corporate sector down with debt. . . .

This bias is evident not just in the interest on reserves that the Fed pays to banks — profits that should be returned to the Treasury — but in its use of quantitative easing.

In response to the 2008–09 financial crisis, the Fed bailed out profligate megabanks by issuing over $2 trillion in reserves, simply by creating the money on a computer screen. Congress, the White House, and the Treasury all acquiesced. But when it was proposed in 2013 that the government bail itself out of its budget woes by minting two trillion-dollar coins, the Federal Reserve said it would not accept the Treasury’s legal tender; and the White House again acquiesced. Somehow it has become acceptable for the Fed to create money for banks, but not for the Treasury to create money for the people — although the Constitution explicitly empowers it to do so.

Inflation Safeguards

Trillion-dollar coins can evoke images of million-mark notes filling wheelbarrows. But as Prof. Hudson has observed, “Every hyperinflation in history has been caused by foreign debt service collapsing the exchange rate. The problem almost always has resulted from wartime foreign currency strains, not domestic spending.”

Critics point to the COVID-19 stimulus checks as proof that increasing the circulating money supply causes inflation. But a cross-country study published in 2024 by Olivier Blanchard and Ben Bernanke and another by Brookings economists showed that the 2021–22 spike was driven mainly by supply shocks in food and energy, not excess demand.

Whether minting trillion-dollar coins would inflate consumer prices depends on how the funds are used. Conventional theory says that inflating the money supply inflates prices — “too much money is chasing too few goods.” But the converse is also true: if the new money is invested in domestic manufacturing, construction and infrastructure, it can stabilize prices by expanding productive capacity, increasing supply.

This principle was demonstrated in a 1997 paper by U.K. Prof. Richard Werner titled “Towards a New Monetary Paradigm: A Quantity Theorem of Disaggregated Credit.” Drawing on Japanese data, he showed that credit needs to be split into two separate circulations:

• Productive credit — loans for factories, R&D, and infrastructure — which tracks GDP growth almost one to one without raising consumer prices.

• Financial credit — loans for asset speculation — which fuels bubbles and crashes.

When the government pays $1 trillion a year in interest, that money flows into financial markets, bidding up assets and widening inequality. It does not build factories, housing, or infrastructure. Retiring interest-bearing debt with a non-interest-bearing coin thus removes a major inflation driver.

New money created by the government to retire existing debt would go to bondholders, most of whom are institutional investors, pension funds, or foreign central banks. They are not buying groceries. Their goal is to invest their profits or savings in a secure vehicle that pays some interest. If their bond money were returned to them, they would no doubt just shift the funds to some other low risk investment vehicles, perhaps municipal bonds or money market funds.

Meanwhile, the Treasury’s savings could be redirected into infrastructure, domestic manufacturing, and development, expanding supply in domestic markets, causing supply to rise with demand and keeping prices stable.

China’s Precedent

Among other precedents, China’s remarkable growth is the closest modern parallel to what U.S. government-issued currency focused on infrastructure and development could achieve. From Jan. 1996 to Sept. 2025, China’s M2 money supply grew by 5,600% (from 5,840.10 CNY Billion to 98,146.60 CNY Billion), while consumer price inflation averaged under 2%. New money was channeled into fixed capital formation — high speed rail (45,000 km built), ports, airports, 5G networks, and housing. The resulting productivity surge absorbed the monetary expansion without price inflation.

Medieval Tally Sticks

England’s tally stick system illustrated the same logic centuries earlier. Tallies — split hazelwood rods recording debts — functioned as currency for seven centuries. The Exchequer created tallies on demand to pay soldiers, builders, and suppliers. The sticks recorded IOUs that circulated as money and were accepted in payment of taxes. The system ended not because it failed but for political reasons. Ironically, when the surplus sticks were burned in 1834 in the furnace beneath the House of Lords, the fire set the building ablaze and destroyed Parliament itself.

Time to Take Back the Money Power

There is simply not enough money in the producing economy to fund the services we desperately need, pay down the debt, and keep taxes affordable. Sovereign government-issued money is constitutional, historically proven, and — if invested in infrastructure, manufacturing and development — can actually be deflationary.

The paper money printed by the central bank and the digital money created by private banks are nowhere mentioned in the Constitution. Only Congress is given the money power — the power “to coin money [and] regulate the value thereof” — a power it executes through the Treasury. If the Federal Reserve resists accepting Treasury-minted high-denomination coins, Congress can require their acceptance by amending the Federal Reserve Act, as it has done several times over the years.

With interest threatening to devour the national budget, Congress’s sovereign power to issue money needs to be exercised with some coins larger than quarters and dimes. Congress needs to mint some trillion-dollar coins, as the Constitution empowers it to do.

STAY INFORMED! Receive our Weekly Recap of thought provoking articles, podcasts, and radio delivered to your inbox for FREE! Sign up here for the HoweStreet.com Weekly Recap.

Ellen Brown December 15th, 2025

Posted In: Web of Debt